For the better part of three decades, the Western intellectual class has treated Japan as a cautionary tale. It is the designated sick man of the developed world, a country ostensibly suffocating under the weight of its own debt, trapped in a deflationary spiral, and, most damningly of all, failing to reproduce. We are inundated with headlines about “ghost villages” and adult diaper sales outpacing baby diapers. The consensus is absolute: Demographics are destiny, and Japan’s destiny is a slow, quiet extinction.

This narrative is not just misleading; it is a fundamental misreading of the 21st century. It relies on 20th-century economic models that overly emphasize population size and growth as the primary drivers, ignoring the tectonic shifts brought about by automation, artificial intelligence, and radical life extension. Japan is not dying. It is evolving. While the West fights culture wars and struggles with the social friction of mass migration, Tokyo is quietly executing the world’s first successful transition into a post-population-growth, high-technology civilization.

The obsession with the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) acts as a blinder. The story isn’t that Japanese women are having 1.2 children; it is that Japanese society has stabilized and had longer to adapt compared to its neighbors who are in freefall. The story isn’t that there are fewer young workers; it is that the definition of “worker” is being rewritten by robotics and a vital, active elderly population that refuses to retire.

We need to dismantle the “Japanification” dismissal. We need to look at comparative demographics, health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE), labor force dynamics, and deep-tech industrial policy. These all demonstrate that Japan is not a relic of the past, but a viable blueprint for the future of the developed world.

The Best House in a Bad Neighborhood

To understand why the Western fixation on Japan is so misplaced, look at the neighborhood. The narrative paints Japan as the unique outlier of demographic collapse. The data, however, reveals that Japan is actually the “best house in a bad neighborhood.” While Japan has managed a soft landing of demographic stabilization, its East Asian peers are currently experiencing a demographic crash of unprecedented velocity.

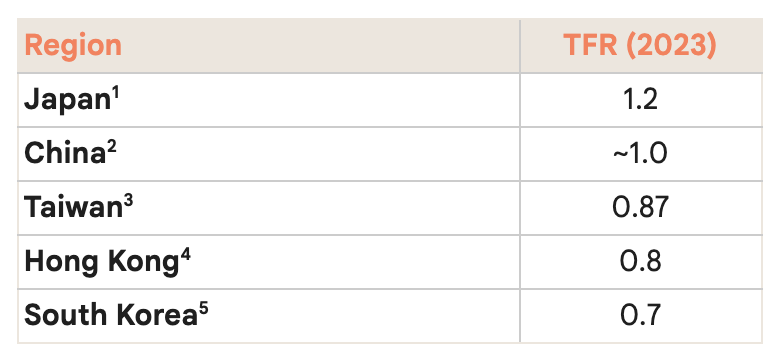

The magic number in demography is 2.1, the replacement rate. Japan has been below this number for decades, currently hovering around 1.2. This is low, certainly. But in the context of East Asian industrialization, it is remarkably resilient.

Contrast this with South Korea. In 2023, South Korea recorded a fertility rate of roughly 0.7. This is not a decline; it is a national catastrophe. A rate of 0.7 means that for every 100 Koreans today, there will be roughly 12 grandchildren. It implies the halving of the population within a single generation. Taiwan and Hong Kong are following the same trajectory, with rates of 0.87 and 0.8 respectively.

Then there is China. For years, observers assumed China would avoid the “Japan trap.” Instead, it has sprinted into it. Official Chinese statistics claim a rate of 1.0, but the real number is likely lower. China is getting old before getting rich, hitting the demographic wall with a GDP per capita a fraction of Japan’s.

Japan’s TFR of 1.2 is the highest in the region, and it entered its demographic transition earlier, in the 1990s, giving it more than 20 years to adjust. The precipitous drops seen in Korea and China suggest profound systemic failures and planning that Japan has largely mitigated.

The haters dismissing Japan become even more suspect when you look at Europe. Italy (1.2)6 and Spain (1.1)7 have fertility rates nearly identical to, or lower than, Japan’s. Yet, we rarely hear the term “Italianification” or “Spanishification.”

When it comes to headlines on aging populations, Japan gets an unfair share considering where it stands relative to peers. And let’s be clear, birth rates are declining around the world ーthis is a universal problem that is not unique to Japan. Some argue that it is because of the dependency ratio, or inverted pyramid problem. But even this doesn’t tell the whole story.

The HALE Hegemony

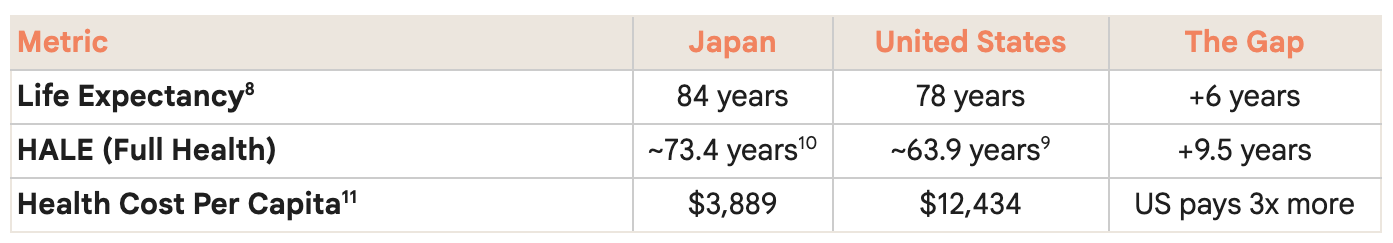

The standard economic model of the “dependency ratio” is a crude instrument. It bifurcates the population into “workers” (aged 15-64) and “dependents” (65+). This binary assumes that on your 65th birthday, you cease to be a producer and become a burden. In the United States, where metabolic health is abysmal, this might be true. In Japan, it is a statistical lie.

Japan has not just extended life; it has extended vitality. To understand the Japanese economy, look at Health-Adjusted Life Expectancy (HALE), the measure of years lived in full health, free from disabling disease or impairment.

Japan possesses the highest HALE on the planet. According to WHO data, the average Japanese citizen can expect to live almost 74 years in full health. This is not “life expectancy”; this is the period of active, functional life.

Compare this to the United States. The U.S. HALE sits at roughly 64 years. This creates a “Vitality Gap” of nearly a decade. A 75-year-old Japanese person often possesses the physiological resilience and cognitive function of a 65-year-old American. 75 is the new 65 baby!

Japan achieves these superior outcomes while spending a fraction of what the U.S. spends. The U.S. healthcare system consumes nearly 18% of GDP for outcomes that rank near the bottom of the OECD. High rates of obesity, opioid addiction, and violence drag down the U.S. average. Japan’s system focuses on preventative care, driven by a cultural emphasis on diet and yearly checkups. Japan is not just aging; it is aging well.

The Silver Working Class Paradox

If demographics were destiny, Japan’s labor force should be shrinking in lockstep with its population. Yet, the data shows the opposite. In 2024, the number of employed individuals in Japan reached a record high of 67.8 million. How does a shrinking country have a growing workforce? Simple: The elderly refuse to quit.

Japan has rejected the Western ideal of retirement as a period of sedentary leisure. Instead, it has embraced a model of lifelong activity. The labor force participation rate for men in Japan is roughly 71.6%, the highest in the G7. For the population aged 65 and over, the employment rate is over 25%, significantly higher than the US (~18%) or the UK (~11%).

This isn’t economic desperation; it’s cultural, rooted in the Japanese sense of pride in one’s work and contribution to society. While French workers riot over a pension age increase from 62 to 64, Japanese workers are voluntarily staying in the workforce well into their 70s.

Alongside the elderly, Japan has tapped into its other great underutilized resource: women. The female labor force participation rate reached a record high of roughly 54% in 2024. The “Womenomics” policies have successfully dismantled many of the barriers to female employment, creating a counter-cyclical force against demographic decline.

Robots, Aliens, and Transhumanism

Everything outlined above is just the baseline defense. The real alpha lies in what the standard economic models fail to price in: the collision of atoms and bits.

Legacy analysis assumes economic growth is tied closely to headcount. It fails to account for the AI revolution—in both software and robotics—which Japan is uniquely and culturally prepared to embrace. It overlooks a calibrated, thoughtful approach to immigration that prioritizes social cohesion over short-term demographic hacks.

Crucially, it ignores the next frontier: the industrialization of the human form itself. We aren’t just talking about better healthcare; we are talking about revolutionary innovations in human enhancement, from bionics and cybernetics to industrial-scale stem cell production. While the West debates the ethics of progress, Japan is quietly building the infrastructure for transhumanism.

The bet is that Japan isn’t dying; it’s upgrading.

I’ll be dissecting the mechanics of this transition and the investment opportunities inherent in it throughout the year. If you want to see what the future looks like before the pundits catch up, subscribe.

References

- https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hh/1-2.html

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=CN

- https://www.ceicdata.com/en/taiwan/social-demography-non-oecd-member-annual/total-fertility-rate-children-per-woman

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=HK

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=KR

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=IT

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=ES

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?locations=JP-US

- https://data.who.int/countries/840

- https://data.who.int/countries/392

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?locations=JP-US